The Best Canadian Fiction and Poetry of 2017

Transit, by Rachel Cusk (HarperCollins) – In this follow-up to her Scotiabank Giller Prize-shortlisted novel Outline, a woman and her two sons move to London after the end of her marriage. Transit, too, was a finalist for this year's Giller. As reviewer Pasha Malla notes, it's a novel "that should resonate with anyone … and a story we should all be able to recognize as our own."

The Lonely Hearts Hotel, by Heather O'Neill (HarperCollins) – A love story, between two talented but star-crossed orphans, set in the seedy underbelly of Montreal in the early 20th century. Once again, says reviewer Jack Kirchoff, O'Neill's "narrative [is] wrapped in her eloquent, elevated prose, with her trademark gift for inspired, unusual but totally apt metaphors and similes." The novel proves, he writes, that she's "just getting better and better."

Son of a Trickster, by Eden Robinson (Knopf Canada) – In the first part of a proposed trilogy – and a finalist for the Giller Prize – a young man learns of his unusual parentage. Nathan Whitlock calls it "a black comedy about the irredeemably messed-up life of a teenager in small-town British Columbia."

American War, by Omar El Akkad (McClelland & Stewart) – This debut novel, which was a finalist for the Rogers Writers' Trust Fiction Prize, presents a nightmarish vision of a fractured America, a century from now, and the ways in which violence changes a person. Lawrence Hill calls it "astounding, gripping and eerily believable."

Lost in September, by Kathleen Winter (Knopf Canada) – A traumatized soldier, who may or may not be General James Wolfe, wanders the streets of present-day Montreal in a novel reviewer Spencer Gordon calls "a touching portrait of a broken man, as well as a considerable addition to the literature of war, of trauma and recovery."

We'll All Be Burnt in Our Beds Some Night, by Joel Thomas Hynes (HarperCollins) – The winner of this year's Governor-General's Literary Award for English-language fiction, in which an ex-con embarks on a cross-country road trip with his girlfriend's ashes, is "a potent and precise manual of how human disasters are made," Alix Hawley says. "Hynes's gift is in serving up the pieces of the story to fall as they will, leaving you to assemble the smash.

This Accident of Being Lost, by Leanne Betasamosake Simpson (House of Anansi) – This collection of songs, stories and poems was a finalist for the Rogers Writers' Trust Fiction Prize and established Simpson as one of the country's most important new Indigenous voices. "Her writing educates the reader even as it admits to not having all the answers," Phoebe Wang says. "I welcomed having my assumptions about urban Indigenous people upended, and this is accomplished with the nourishing humour, wisdom and poetic, loose-limbed lines that have been sewn through the stories."

Next Year, For Sure by Zoey Leigh Peterson (Doubleday Canada) – This Giller Prize-longlisted debut, in which a couple explores polyamory, "is a thoughtful, warm meditation on what it means to love, querying our widespread cultural reluctance to expand our definitions beyond traditional narratives and typical pairings," Stacey May Fowles writes.

Bellevue Square, by Michael Redhill (Doubleday Canada) – In the winner of this year's Giller Prize, a woman becomes obsessed with her (possible) doppelganger. "In its taut span of 262 pages, Bellevue Square features several narrative and tonal hairpin turns," José Teodoro writes. "With each of these, our admiration for Redhill's storytelling dexterity burgeons …"

Brother, by David Chariandy (McClelland & Stewart) – This powerful portrait of two brothers growing up in Scarborough in the early 1990s won the the Rogers Writers' Trust Fiction Prize. Writes Hannah Sung: "Brother is filled with moments of swagger and bravery, of recklessness and love that sparks against the dull pain of tragedy, which is foretold in elegiac descriptions of the landscape."

The Corpses of the Future, by Lynn Crosbie (House of Anansi) – The risk-taking poet's latest collection, born out of her father's battle with dementia, "is both unswerving in honesty and high in impact," Canisia Lubrin writes. "This 140-page grief-song makes for a most dangerous and essential reading experience."

The Sun and Her Flowers, by Rupi Kaur (Simon & Schuster) – The young writer's first collection, Milk and Honey, catapulted her to global fame; her second collection has been glued to the bestsellers lists since it was published this fall. "Once again," Mark Medley writes in a profile of Kaur, "her poems explore issues of love, and trauma, and family, and gender, and finding a place in the world."

Bad Endings, by Carleigh Baker (Anvil Press) – This debut collection of stories was a finalist for the Rogers Writers' Trust Fiction Prize, and winner of the City of Vancouver Book Award. Says Jade Colbert: "Baker, who is Cree-Métis/Icelandic and was raised on Sto:lo territory, writes about the West Coast as an informed guest, a keen observer of contradiction and its implications."

So Much Love, by Rebecca Rosenblum (McClelland & Stewart) – This debut novel focuses on a twentysomething woman's kidnapping and the possibly linked disappearance of a young man, and its effect on the small town where they live. The novel, Marsha Lederman writes, "approaches its subject and tells its characters' stories with so much heart and sharp efficiency that you can sit down with it for a day and feel a shift in the way you look at life. You will not want to put it down."

Minds of Winter, by Ed O'Loughlin (House of Anansi) – A historical epic about the Franklin expedition, among other threads, that skips around the globe, as well as through the decades, was a finalist for this year's Giller Prize. It's a "hugely ambitious novel," Ken McGoogan writes, and O'Loughlin "displays a prodigious imagination in creating, from scratch, one stand-alone scene after another."

My Ariel, by Sina Queyras (Coach House Books) – A meditation on the life and legacy of Sylvia Plath through a "repurposing" of her best-loved work. Writes Phoebe Wang: "Few poets are better equipped than Queyras to plunge into the examination of the figure of Plath as a prototype for female genius. With honesty, humour and passionate attention, she lays bare the gendered conventions that circumscribed Plath's life and how they are still, in new guises, determining her own life as well as that of her female students."

In the Cage, by Kevin Hardcastle (Biblioasis) – A retired mixed-martial artist tries to provide a good life for his wife and young daughter in Hardcastle's debut novel. Writes J.R. McConvey: "Whether you like a fight or not, chances are, something in this novel will move you. In the Cage is a fierce, beautiful book."

Demi-Gods, by Eliza Robertson (Hamish Hamilton) – This lyrical debut novel explores the troubling and sexually charged relationship, over the years, between two sisters and their step-brothers. Writes Alix Hawley: "[Robertson] juxtaposes grime and glory, from dirty underwear to ocean phosphorescence, to beautifully disturbing effect. Set in the 1950s and 60s, Demi-Gods is atmospheric without historical overload."

Scarborough, by Catherine Hernandez (Arsenal Pulp Press) – An "ambitious collection of intertwined stories" that "tries, valiantly, to render unseen people, finally, seen," according to Hannah Sung, Hernandez brings the Toronto suburb to life by a chorus of diverse voices. A finalist for this year's Toronto Book Award.

The Original Face, by Guillaume Morissette (Esplanade Books) – A "cash-strapped 29-year-old internet artist" is at the heart of Morissette's second novel. Says Jade Colbert: "What makes Morissette's novel different is how Daniel's online life is the content of his real life, not its opposite, and how Morissette conveys this as worthy of the novel's attention, without gimmicks. It's also very, very funny."

The Shoe on the Roof, by Will Ferguson (Simon & Schuster) – A grad student seeks to "cure" three self-described Messiahs in Ferguson's first novel since winning the Giller Prize. Writes Alix Hawley: "Ferguson certainly has a broad comic streak … but here, the author's true interest is in going into the dark, interrogating the nature of mind, faith, love and reality, and taking the novel down a philosophical road."

Admission Requirements, by Phoebe Wang (McClelland & Stewart) – An assured debut book of poetry, reviewer Stevie Howell calls the collection "a lyrical meditation on identity, migration, family and community" that "announces Wang's incomparable voice and vision, as she proceeds to break new ground on every page."

Fugue States, by Pasha Malla (Knopf Canada) – A tale of two childhood friends who (separately) journey to Kashmir. Writes David B. Hobbs: "What starts as a critique of Canadian culture through the lens of a second-generation family becomes a funny, brutal and strange commentary on the relationship between power and storytelling."

Little Sister, by Barbara Gowdy (HarperCollins) – The owner of a Toronto cinema strangely and inexplicably begins to enter the body of another woman in Gowdy's first novel in a decade. "It is fun and funny and can frequently startle you, breaking your heart with the lovingly observed minutia of everyday experience," José Teodoro says. "Its confluence of the uncanny and the ordinary, of mischief and profundity, at times recalls the books of Haruki Murakami or the films of Woody Allen, but Gowdy's use of quirk as an entrée into psychological depth is most closely akin to the stories of Lorrie Moore. Little Sister is all depth and grace and yet never more than a sentence away from a playful nudge in the ribs."

The Dark and Other Love Stories, by Deborah Willis (Hamish Hamilton) – Reviewer Steven W. Beattie positively compared this second collection of stories to the work of Alice Munro: "Willis's adeptness at modulating the tone and mood of her story owes much to Munro, as does the irony in her collection's title: The Dark is explicitly identified as a love story, although like the 10 pieces that accompany it, the version of love on offer is perilous and liable to shatter at any moment. Nor is it confined to the arena of romance, although a number of stories do address that aspect of the subject."

The Best Canadian Non-Fiction of 2017

Black Edge: Inside Information, Dirty Money, and the Quest to Bring Down the Most Wanted Man on Wall Street, by Sheelah Kolhatkar (Random House) – The New Yorker staff writer's exploration of Wall Street trader Steven A. Cohen and the 2008 financial meltdown. "Thrillerish in its construction, terse in its prose, the book is grounded by brilliant reporting and enlivened by Kolhatkar's storytelling nous," Richard Poplak writes.

The Last Word: Reviving the Dying Art of Eulogy, by Julia Cooper (Coach House Books) – This study of how we grieve, born out of her mother's death when the author was just 19, is a "whip-smart rumination on death," reviewer Isabel B. Slone says. "It feels cathartic to read a book that goes deep on a subject that most people are either too awkward or too polite to broach in pleasant company."

Juliet's Answer: One Man's Search for Love and the Elusive Cure for Heartbreak, by Glenn Dixon (Simon & Schuster) – A memoir of moving to Verona to respond to letters sent to Shakespeare's Juliet. "Dixon has gracefully entered into the tradition of travel writing meets memoir (think Eat, Pray, Love,) and despite his driving belief that he knows so little about the subject, he writes about love with admirable generosity, sensitivity and insight," Stacey May Fowles writes.

The Reconciliation Manifesto: Recovering the Land, Rebuilding the Economy, by Arthur Manuel and Grand Chief Ronald Derrickson (Lorimer) – The late Indigenous activist and leader provides a vital blueprint, which reviewer Carleigh Baker calls "one of the most important texts on truth and reconciliation ever written. The Reconciliation Manifesto is a cogent step-by-step look at how Canada's colonial past created our present situation, and provides decolonizing strategies for the future."

Baseball Life Advice: Loving the Game That Saved Me, by Stacey May Fowles (McClelland & Stewart) – A collection of essays celebrating the sport of summer. "Like so many baseball writers, Fowles is at her strongest when she's at her most personal and granular," Eric Andrew-Gee writes. "At its best, it's a catalogue of feeling, from enthusiasm and anger to anxiety and heartache – which is to say it's a book about love."

Life on the Ground Floor, by James Maskalyk (Doubleday Canada) – The Toronto doctor's latest memoir, and the winner of this year's Hilary Weston Writers' Trust Prize for Non-Fiction, is a book that "captures the viscera, real and symbolic, of the ER – its sights, sounds, smells, pulse – without romanticizing the work," André Picard writes.

Arrival: The Story of CanLit, by Nick Mount (House of Anansi) – An in-depth study of Canadian literature through the writers who cemented its reputation. "Mount writes accessible biographies of the major players in this developing universe," David Staines says. "There are many details in the lives one knows, many details one does not know and his enterprise is a kaleidoscope of fascinating people who shaped our country's growth into a literature respected around the world."

Too Much and Not the Mood, by Durga Chew-Bose (HarperCollins) – A sharp collection of essays from an essential new voice. Writes Stacey May Fowles: "The reader knows immediately that this collection is the product of an observant and inventive mind, someone with a knack for breaking down big ideas and expanding on minor details in a way that makes them meaningful – even revelatory."

The Whisky King: The Remarkable True Story of Canada's Most Infamous Bootlegger and the Undercover Mountie on his Trail, by Trevor Cole (HarperCollins) – Rollicking historical true crime from an award-winning novelist. Says Taras Grescoe: "The Whisky King has got it all: poison hooch in blind pigs, liquor orgies with double-crossing dames, shootouts in chicken coops. This is superb non-fiction, by a writer at the top of his game."

The Handover: How Bigwigs and Bureaucrats Transferred Canada's Best Publisher and the Best Part of Our Literary Heritage to a Foreign Multinational, by Elaine Dewar (Biblioasis) – How did the famed Canadian publishing house McClelland & Stewart wind up controlled by a German conglomerate? Roy MacSkimming writes that Dewar has "written a case study in public-interest journalism, showing how to break a story open by refusing to be cowed by power and refusing to take no for an answer."

I Hear She's A Real Bitch, by Jen Agg (Doubleday Canada) – The Toronto restaurateur's first book is part memoir, part manifesto, but a must-read. "If a generation of cooks followed Kitchen Confidential into the industry on the promised glory of good times and hard living," Chantal Braganza writes, "for largely different reasons – because restaurant ownership is so desperately lacking in diversity, and because kitchen culture could sure use a change – with hope, I Hear She's a Real Bitch will do the same."

Birds Art Life, by Kyo Maclear (Doubleday Canada) – The novelist and picture-book author offers an introspective memoir of birding and the artistic life. The book, Stacey May Fowles says, "finds beauty and enjoyment in unlikely places, and contentment in the smallest things – from the flight of a bird to the love of a parent to the sweetness of a song."

Curry: Eating, Reading, and Race, by Naben Ruthnum (Coach House Books) – An exploration of food, ethnicity and fiction. "Ruthnum marries his sarcastic wit with fascinating history and prescient observations about pop-culture representations of Indian-ness," writes Manisha Aggarwal-Schifellite, who adds that the "book is an engaging and entertaining examination of fiction and his voice is a welcome addition to the discussion. He doesn't boast to have all the answers, but he has a few solutions."

Out Standing in the Field: A Memoir by Canada's First Female Infantry Officer, by Sandra Perron (Cormorant Books) – A "revealing and moving memoir" by Canada's first female combat soldier. Says Matti Friedman: "Perron writes like a combat soldier – factual, direct and close to the ground, a that is effective in getting her experience across without artifice."

Run, Hide, Repeat: A Memoir of a Fugitive Childhood, by Pauline Dakin (Viking) – You think your childhood was weird? Dakin, a long-time CBC reporter, has you beat. Jade Colbert calls it "a well-paced and engrossing memoir" that "describes the isolating effects of a childhood on the run and a young adulthood spent constantly looking over her shoulder."

One Day We'll All Be Dead and None of This Will Matter, by Scaachi Koul (Doubleday Canada) – A hilarious, acerbic and surprisingly emotional collection of essays that tackles everything from sexism to self-care. "She weaves stories, which through their cultural uniqueness and specificity, become universal and applicable to all," Zarqa Nawaz writes.

Hoover: An Extraordinary Life in Extraordinary Times, by Kenneth Whyte (Knopf) – The Herbert Hoover story is a distinctly American tale: persistence, ambition, grand plans played out over five continents and marked by three economic crises. "Whyte serves as a learned but inviting tour guide to this extraordinary life," reviewer David Shribman writes, "bringing a fresh eye and fresh perspective to an engineer who balked at social engineering, a man of great repute until he defeated Al Smith for president and then watched his reputation be dissipated and then destroyed."

Game Change: The Life and Death of Steve Montador, and the Future of Hockey, by Ken Dryden (Signal) – A deep piece of investigative journalism that chronicles the emotional rise and quick demise of one of hockey's many tragic figures. Here, reviewer Brett Popplewell writes, is Dryden, one of hockey's most celebrated goalies, "reclaiming his place among this country's deepest sports writers." To Dryden, he adds, "Montador's story is the story of modern hockey. That of a grinder who sacrificed everything for the game."

The Unfinished Dollhouse: A Memoir of Gender and Identity, by Michelle Alfano (Cormorant Books) – The author shares the bitingly personal, viscerally honest story of dealing with her child's transition. Reviewer Michael Coren says "it must have been a supremely difficult book to write, because she is a participant rather than a spectator, and as the mother of a girl is involved at the most intimate level with every aspect of Frankie finding resolution as a man. … At its core is the timeless message of absolute and unconditional love."

Gutenberg's Fingerprint: Paper, Pixels and the Lasting Impression of Books, by Merilyn Simonds (ECW) – Gutenberg's Fingerprint does for our books what Margaret Visser's Much Depends on Dinner did for the food on our plates, reviewer Michael Harris writes: "Each ingredient is revealed in all its complicated glory, with sections on paper, type, ink, presses and finished books." Ultimately, he says, "Simonds's work is less a celebration of bookmaking and more a celebration of the base human instinct for storytelling, for the sacredness of expression in whatever form.

Sean Rogers's Favourite Comics and Graphic Novels of 2017

Everything is Flammable, by Gabrielle Bell (Uncivilized Books) – When her mother's house burns down in the wilderness of northern California, Bell travels cross-country to help get her back on her feet. Prodding at sore memories and quizzing misfit neighbours, Bell finds ample fuel for her intimate, scrupulous diary comics.

Hostage, by Guy Delisle, translated by Helge Dascher (Drawn & Quarterly) – In detailing a Médecins sans frontières staffer's captivity in the Caucasus, Delisle dwells expansively on what keeps us human, even in the most straitened of circumstances. This claustrophobic portrayal of a man confined to a room for months on end is also, paradoxically, a riveting action comic.

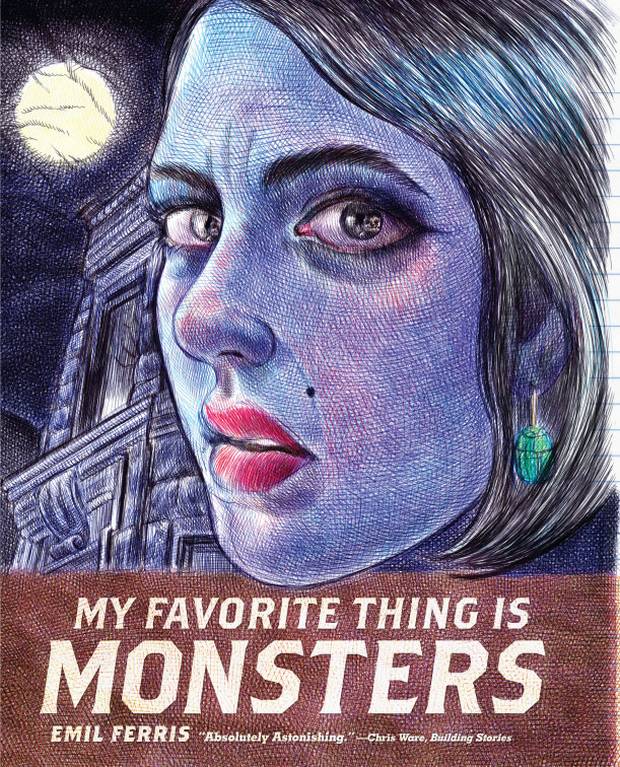

My Favorite Thing is Monsters, by Emil Ferris (Fantagraphics) – Ferris's remarkable debut is many things – a detective yarn, a Holocaust survivor's tale, a coming-out story – but most obviously, it's a treat for the eyes. With her resonant pastiches of monster movies and modernist masters, the artist joins the first rank of cartoonists.

Pretending is Lying, by Dominique Goblet, translated by Sophie Yanow (New York Review Comics) – Goblet's expressionist reflections on fraught relationships – with her aloof partner and alcoholic father, especially – look tattered by life, distorted by volatile emotions and hazy recollections. Released in French a decade ago, Goblet's groundbreaking work still feels raw and new.

Songy of Paradise, by Gary Panter (Fantagraphics) – The punk art pioneer follows up his versions of Dante's Inferno and Purgatory by adapting John Milton's Paradise Regained, irreverently replacing the Son of God with a truculent bumpkin. Every oversized page is a marvel, fervent and visionary and bitterly funny.

Jade Colbert's Favourite Canadian Small-Press Books of 2017

Seven Fallen Feathers: Racism, Death, and Hard Truths in a Northern City, by Tanya Talaga (House of Anansi) – The funding gap between Indigenous and Canadian children is the federal government's responsibility. Talaga's book is about how this gap kills Indigenous kids. Though set in Thunder Bay, it's a national story and a national disgrace. Canadians need to listen.

Dr. Bethune's Children, by Xue Yiwei, translated by Darryl Sterk (Linda Leith Publishing) – An unsuccessful attempt at an "authentic" biography of Canadian physician Norman Bethune leaves a Chinese writer (who, like the author, lives in Montreal) musing on the lost children of the Cultural Revolution. A Canadian novel on a shared Canadian-Chinese legacy.

The Clothesline Swing, by Ahmad Danny Ramadan (Nightwood Editions) – Scheherazade keeping Death at bay, an old man feeds stories to his dying lover nearly four decades after they fled Syria in 2012. A love letter to storytelling and to gay Damascus, Ramadan's novel is a moving portrait of life in exile.

Sputnik's Children, by Terri Favro (ECW) – Favro channels childhood anxieties about the threat of nuclear attack into this novel about a possible alternative Cold War. Influenced heavily by a comic-book aesthetic, beneath the taut, fun storyline of Sputnik's Children is sharp social commentary.

The Bone Mother, by David Demchuk (ChiZine) – There are fabulous beings and then there are monsters. The horror in Demchuk's novel (the first horror book nominated for the Giller) is that the monsters of the Second World War come to present-day Canada. "Some stories need to be told time and again."

Jade Colbert's Favourite Debuts of 2017

Ghachar Ghochar, by Vivek Shanbhag, translated by Srinath Perur (Penguin) – A deceptively simple story about a man from Bangalore, India, whose family sponges off an uncle's spice business that turns out to have been ghachar ghochar ("irredeemably tangled") in something much darker all along. The startling English-language debut of Kannada writer Shanbhag.

Things We Lost in the Fire, by Mariana Enriquez, translated by Megan McDowell (Hogarth) – One of two high-profile English debuts by female Argentinian writers in 2017 (the other, another McDowell translation, Fever Dream), Enriquez's gothic collection disinters skeletons from Argentina's Dirty War, but most haunting of all is the country's present.

Kintu, by Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi (Transit Books) – A curse unleashed in 1750 comes down on members of a Ganda clan, forcing a scattered family to come together and allowing author Makumbi an excellent premise for a novel addressing the workings of history in multifaceted modern Uganda.

The Accusation: Forbidden Stories from Inside North Korea, by Bandi, translated by Deborah Smith (House of Anansi) – J'accuse! Billed as the first work of fiction by someone still living in North Korea (under a pen-name meaning "firefly"), Bandi's collection set during the Arduous March of the early 1990s is understated, detail-rich, full of pathos and incredibly brave.

Dead Reckoning: How I Came to Meet the Man Who Murdered My Father, by Carys Cragg (Arsenal Pulp Press) – Twenty years after her father's death, Cragg opened contact with his murderer, seeking answers only he could provide. Cragg's search for truth opens important questions on victim's rights, the nature of justice and how to repair harm.

Margaret Cannon's Favourite Crime Fiction of 2017

The Thirst, by Jo Nesbo (Random House Canada) – Harry Hole has left the force, determined to lead a quiet life and please his lover. But then a case comes that only Norway's lone serial killer specialist can solve. Two completely disparate women have been murdered and the only clue is that they were both registered on Tinder. Great gumshoe novel and one of Nesbo's best ever.

Glass Houses, by Louise Penny (Minotaur Books) – A shadowy figure appears on the square in Three Pines. Everyone sees it, but no one speaks. What they all sense is a deep feeling of dread. When a dead body appears, no one is surprised. Penny's best book so far.

The Child Finder, by Rene Denfeld (HarperCollins) – A child is lost. After three years, and an exhaustive police search, her parents are desperate for an answer. Dead or alive, they want to know what happened. They call in Naomi, a child finder, who represents their last chance. This is a great debut by a brilliant new talent.

The Midnight Sun, by Cecilia Ekback (HarperCollins) – Ekback made a spectacular debut with Wolf Winter, a novel of suspense set in the north of Sweden in 1850. The Midnight Sun takes us back to the same hamlet where the mountains seem fraught with dread and death is always just an accident away. The sequel is almost (but not quite) better than its predecessor.

The Borrowed, by Chan Ho-kei, translated by Jeremy Tiang (House of Anansi) – A series of six novellas, each featuring a case for Kwan Chun-dok, "the Eye of Heaven" who can solve a case while he's in a coma. The novellas cover a 50-year career in reverse order staring in 2013. The ratiocination is great but along the way we get some insight into the culture and history of Hong Kong. There are touches of Sherlock Holmes and the legendary Chinese detective Judge Dee, but it's really Hong Kong that's the star.

Shannon Ozirny's Favourite Young Adult Books of 2017

The Marrow Thieves, by Cherie Dimaline (Dancing Cat Books) – Every year there is a genius book that no one sees coming. In 2017, it was The Marrow Thieves. Winner of the Governor-General's Literary Award and the Kirkus Prize, this wrenching and gutsy apocalypse story from an Indigenous perspective is a legitimate gamechanger.

That Inevitable Victorian Thing, by E.K. Johnston (Dutton Books for Young Readers) – Johnston is a literary chameleon and staggeringly versatile. This year she took on an alternate history that plunges present-day Muskoka into the Victorian era, while still incorporating some breathtaking modern twists.

Undefeated: Jim Thorpe and the Carlisle Indian School Football Team, by Steve Sheinkin (Roaring Brook Press) – A master of finding unbelievable stories in the heart of forgotten histories, Sheinkin tells the true story of Jim Thorpe, one of the world's greatest and unknown athletes. You won't be able to stop talking about this book.

The Agony of Bun O'Keefe, by Heather Smith (Penguin Teen) – The nostalgia you feel when reading this novel about a Nova Scotia girl who finds herself homeless feels like the piercing first notes of those 1980s Hinterland Who's Who animal commercials. Painful, gorgeous and deeply Canadian.

The Hate U Give, by Angie Thomas (Balzer + Bray) – Thomas's debut shattered the YA ceiling and was the book everyone had to read this year – with good reason. Rooted in racism and tragedy, it's also a touching, hilarious story of family. Worth the hype, and then some.

Marissa Stapley's Favourite Commercial Fiction of 2017

We All Love the Beautiful Girls, by Joanne Proulx (Viking) – This is the book I'm recommending to everyone this year – especially friends in book clubs. Beautiful, searing and relevant – shatteringly so, more so every day – this novel explores the unravelling of a marriage when tragedy strikes. But it's about more than marriage, more than this family alone. It's also about the dangers of toxic masculinity, the power imbalance between the sexes and why doing something about these things matters.

Hum If You Don't Know the Words, by Bianca Marais (G.P. Putnam's Sons) – Written with grace and compassion by a debut Canadian novelist, this book was comforting and enlightening at the same time. It's set in South Africa during apartheid and shines a light on the often vicious unrest of the 1976 Soweto uprisings while offering a balm in the form of a tender relationship formed out of necessity and heartache between a British child and her Xhosa caregiver.

All Grown Up, by Jami Attenberg (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt) – Attenberg is an understated master and this was one of the most authentic works I read all year, a perfect book about an imperfect character navigating her late 30s with none of the things she thought she'd have – husband, house, glittering career as an artist – when she was perhaps not naive but at least more optimistic. And yet, there is hope in this often dark novel that feels like being told everything, absolutely everything, about a stranger – and knowing you understand her completely as she walks away.

This Is How It Always Is, by Laurie Frankel (Flatiron Books) – This novel about a transgender girl growing up in a rowdy family of boys is a must-read for anyone who wants to understand the agony and beauty of being this child – or of being her parents. (As for those who don't want to understand? Try to convince just one of those people to read this and you'll have made the world a better place.) And although this is a novel with a message, it's not heavy-handed. It reads like a family caper – think The Royal Tenenbaums or Commonwealth – and is truly unforgettable for both its plot and its compassion for its subjects.

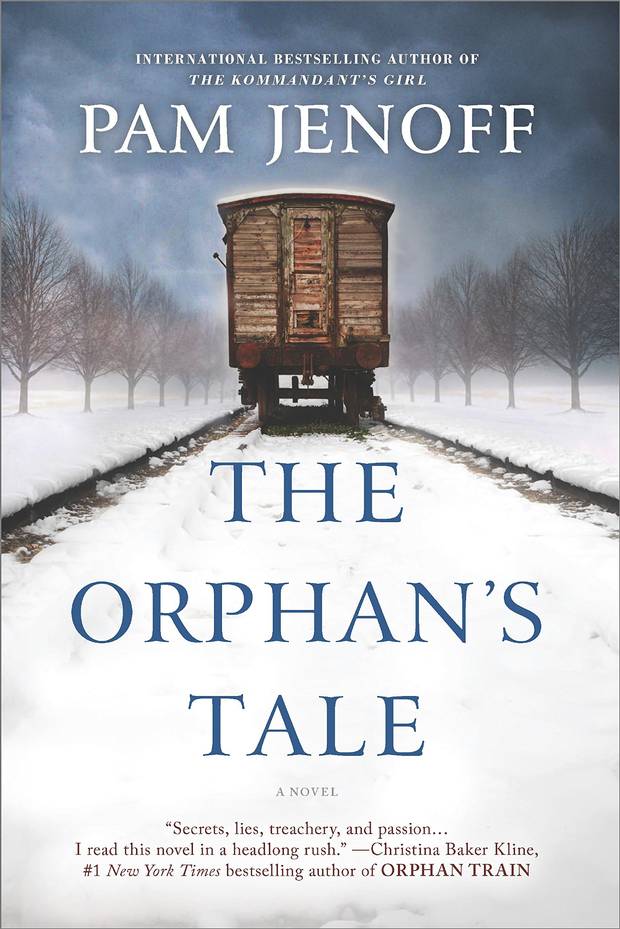

The Orphan's Tale, by Pam Jenoff (Mira) – Set in German-occupied Netherlands during the Second World War, this book begins when 17-year-old Noa, heartbroken after being forced to give up her child, finds a railway car filled with orphaned Jewish infants. Her impulsive decision to take one of the babies sets the story in motion. She must flee and ends up joining a travelling circus, which is the perfect backdrop for this evocative story about the power of love.

Anna Fitzpatrick's Favourite Picture Books of 2017

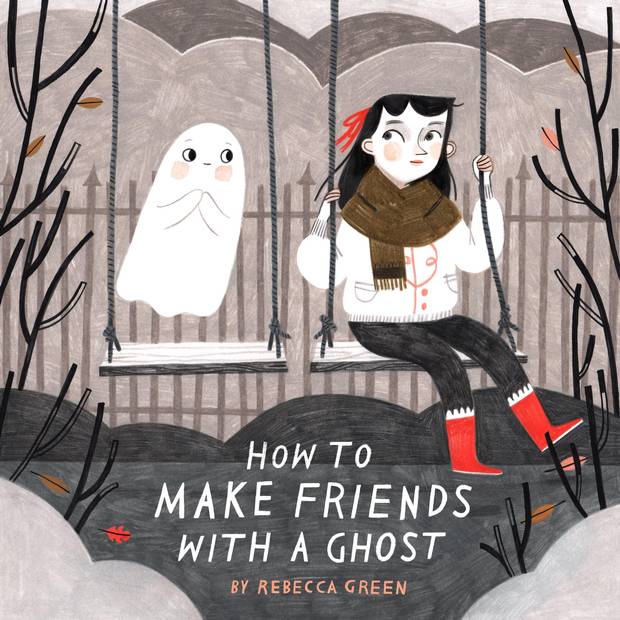

How To Make Friends with a Ghost, by Rebecca Green (Tundra Books) – More adorable than spooky, more funny than creepy, this picture book written as a how-to guide will appeal to sensitive and introverted children who can still appreciate a few good gross-out jokes.

Yak and Dove, by Kyo Maclear and Esme Shapiro (Tundra Books) – Whimsical watercolours accompany this trio of tales about two creatures who are so different they can only be best friends. The sheer attention paid to world-building and background characters makes one hope this book is just the first in a new series.

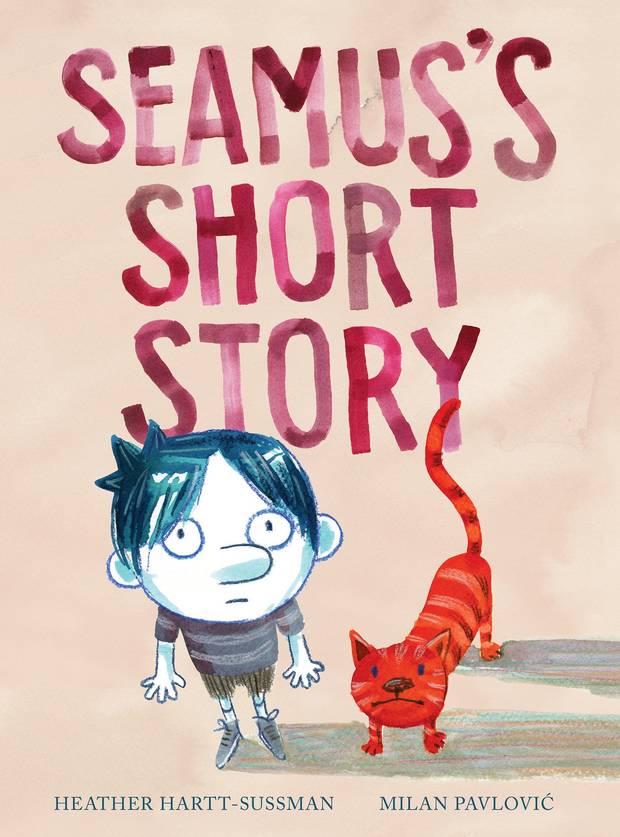

Seamus's Short Story, by Heather Hartt-Sussman and Milan Pavlovic (Groundwood Books) – Hartt-Sussman takes an imaginative and lighthearted approach to this story about self-expression and gender identity, in which frustrated Seamus starts dressing up in his mother's high heels in order to experience life as a taller person.

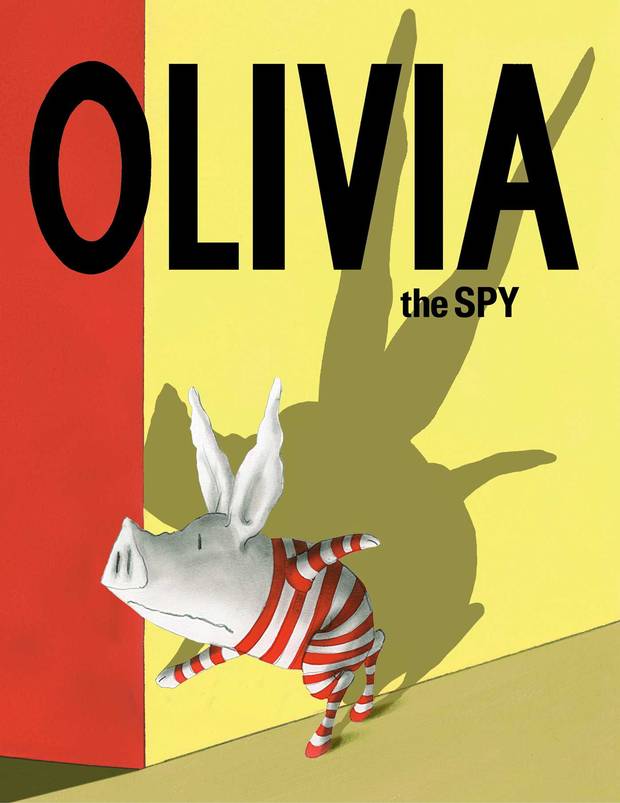

Olivia the Spy, by Ian Falconer (Atheneum/Caitlyn Dlouhy Books) – Olivia the pig is back and as plucky and self-assured as ever. Although she is typically one to stand out, here she is on a mission to blend in. The results, which include disguising herself as a Rothko and crashing the ballet, are pure Olivia.

The Gold Leaf, by Kirsten Hall and Matthew Forsythe (Enchanted Lion Books) – Delicate and intricate illustrations – including actual gold leafing technique – bring to life this simple story about animals in the forest learning about the futility in trying to own a piece of nature.

The Best International Fiction of 2017

The End of Eddy, by Édouard Louis, translated by Michael Lucey (Farrar, Straus and Giroux) – A different side of France is shown in a story of brutality and violence, of small minds and profound sexism and homophobia. Reviewer Bert Archer calls it "the ground-level story of a new subversive force in the West, born of an abandoned working class, that's fuelling a whole new kind of revolution." Ultimately, "Louis doesn't dwell too much on the abstract. His France is a brutal France, and one that takes pleasure in its brutality."

Lincoln in the Bardo, by George Saunders (Random House) The Man Booker Prize winner, Saunders's first novel is an imaginative work about a haunted Abraham Lincoln and a singular piece of American storytelling. "Saunders's brilliance," reviewer John Semley says, "emerges in his understanding that it is not just our status as walking, talking, thinking, bleeding human beings that unites us, but our sorrow." He adds that "Saunders offers the faint, phantasmal hope that a nation long dead may somehow redeem itself; that America may yet howl back triumphantly, from somewhere beyond the grave."

The Redemption of Galen Pike, by Carys Davies (Biblioasis) – The Welsh writer's latest short-story collection tends toward elliptical titles: Jubilee, Myth, Bonnet, Precious, Creed. "She forces her reader to pay close attention and frequently to fill in the blanks in stories that often circle around their central subject," reviewer Steven W. Beattie writes. "This requires a deft hand and superb control, and Davies evinces both; the stories in The Redemption of Galen Pike are tiny marvels of technique and language."

Forest Dark, by Nicole Krauss (HarperCollins) – A suspenseful novel that explores the lives of an American writer and a missing lawyer. Of Nicole Krauss's first novel since her 2010 National Book Award finalist Great House, reviewer José Teodoro says he "felt grateful" for a non-linear journey "through insightful and sometimes moving meditations on marriage and its myriad pitfalls, through the pleasures of secrets, hoaxes and multiverses and the perils of the solipsism that accompany such pondering."

Manhattan Beach, by Jennifer Egan (Scribner) – The Pulitzer Prize-winning author tackles the well-worn themes of precarious familial bonds, secrets and lies, love and lust, abandonment and individualism. "What is revelatory," reviewer Stacey May Fowles writes, "is how beautifully drawn, vivid and moving this familiar setup is when crafted by Egan's skilled hand. Although the basic structure and setting is perhaps standard, her talent renders it anew – making Manhattan Beach a sparkling, lush epic of a novel."

Homesick for Another World, by Ottessa Moshfegh (Penguin Press) – Unflinching, brutally honest stories that are the chilling opposite of the author's comforting previous effort. "Homesick for Another World tends to subvert likeability at every turn, populated as it is by characters who are rash, desperate, ill-advised and self-destructive," reviewer Pasha Malla writes. "Readers will feel implicated in their foibles, often painfully. But these unflinching, brutally honest stories accomplish what fiction is meant to do."

The Golden House, by Salman Rushdie (Knopf Canada) – His new urgent novel is the story of Nero Golden, a business mogul of dubious character who flees his unnamed hometown, along with his three sons, after the tragic death of his wife. "On the one hand, I was trying to write a big social novel," Rushdie told Mark Medley in an interview. "But I was also trying to write right up against the present moment. And that's a risky thing, I think, to do – for anybody – if you want to write a book that endures."

Exit West, by Mohsin Hamid (Riverhead) – The Man Booker finalist is a quietly exquisite novel about a couple fleeing their war-torn country for a better life. Reviewer Omar El Akkad calls it "a masterpiece of humanity and restraint." He adds that "the novel's core is something more fundamental than the whims of politics – an exploration of human needs so universal, they elevate Exit West from a product of our time to something timeless."

4 3 2 1, by Paul Auster (McClelland & Stewart) – Almost four novels in one about four different Archie Fergusons and their splintered destinies. Reviewer José Teodoro finds the Man Booker shortlisted work "pretty long-winded, indulging in lists and quasi-Knausgaardian minutia and occasionally working in March of Time-like chronicles of sweeping historic events." But readers should carry on. "The investment pays off. And I suspect it only pays off as well as it does in part because of the book's sprawl"

The Ministry of Utmost Happiness, by Arundhati Roy (Hamish Hamilton) – Roy's new novel 20 years after winning the Booker Prize explores the harrowing and complicated aspects of love. Reviewer Durga Chew-Bose says that "to read Roy is to build a sense of wonder, incrementally. To ask questions not of what we we're seeing of late, but what we've been staring at the whole time." She also recommends becoming more familiar with Roy. "It's vital to have at least some sense of her non-fiction; in other words, the past two decades of Roy's work."

The Best International Non-Fiction of 2017

Age of Anger: A History to the Present, by Pankaj Mishra (Farrar, Straus and Giroux) – A history of our present world gone mad, with the author tasking himself with theorizing the source of that rage below the peaks of Trump and Brexit. "Mishra is hardly the first to identify anger as the spirit of the times," reviewer Michael Lapointe writes, "but his book is distinguished by its dogged pursuit of that spirit into its modern origins."

Hunger: A Memoir of (My) Body, by Roxane Gay (Harper) – A profoundly honest account of what it's like to be a woman of size. Reviewer Carly Lewis calls Hunger "one of the most honest texts ever published by a woman in a body of size." She adds that "claiming the space in which to write fiercely about her body, when so few narratives in pop culture's body-acceptance arena are genuine – earned – is powerful."

Between Them: Remembering My Parents, by Richard Ford (HarperCollins) – A collection of two essays on family written 30 years apart, the first focused more on his father, the second on his mother. Ford calls it "an act of love," reviewer Emily Donaldson writes. "That said, any notion of it as non-literary endeavour is undermined by Ford's characteristically elegant prose, his unassuming but sweetly profound phraseology."

World Without Mind: The Existential Threat of Big Tech, by Franklin Foer (Penguin Press) – An exploration of the dangers of tech monopolies and the grim future of intellectual life in an online world. "Foer is smart and trenchant when he attacks," reviewer Michael Harris writes. His solutions are urgent. "The alternative, argues Foer, is an Orwellian morass controlled by a handful of thought authorities."

What Happened, by Hillary Rodham Clinton (Simon & Schuster) – The candidate offers her take on the events that led to the most consequential political upset in recent American history. Reviewer Rachel Giese found that her postmortem "doesn't offer new revelations or theories, but it's still worthwhile." Because "with her guard now down, Clinton is fierce and few are spared."

American Kingpin: The Epic Hunt for the Criminal Mastermind Behind the Silk Road, by Nick Bilton (Portfolio) – A gripping account of the rise and fall of the internet's most notorious black market. Reviewer Richard Poplak called it an "astonishingly well-researched narrative" and said that Bilton's book "will surely emerge as the definitive account of the Silk Road saga."

The Stranger in the Woods: The Extraordinary Story of the Last True Hermit, by Michael Finkel (Knopf) – A stunning account of one man's obsessive withdrawal from society. "Finkel finds a way, in a brief 190 pages, to bring us well beyond the mere facts of the case," reviewer Michael Harris writes. It is, ultimately, "a meditation on the pains of social obligation and the longing toward retreat that resides in us all."

Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI, by David Grann (Doubleday) – An exhaustive investigation into the 1920s conspiracy to wipe out the Osage tribe in oil-rich northern Oklahoma. Reviewer Dean Jobb describes Grann as "obsessed with finding any cold-case evidence that could still be gleaned from yellowing documents and fading memories." The result is a masterful tale that "ensures these brutal crimes will never again be forgotten."

The River of Consciousness, by Oliver Sacks (Knopf Canada) – In this posthumous collection of essay, Sacks revisits a variety of old ideas, from Charles Darwin's underappreciated writings on botany to the contrast between Borgesian and Humean models of time. Reviewer José Teodoro finds the through-line between essays, discovering that "the sole unifying theme is Sacks's unmistakable voice and dizzying array of interests. Which is precisely what imbues this book with such wonder."

Afterglow: A Dog Memoir, by Eileen Myles (Grove Press) – A meditation on the life and death of the author's beloved Rosie the pit bull. "It is not pleasant to visualize how a sweet pit bull named Rosie withered," reviewer Carly Lewis writes, "but it is in this portrayal of decline that the love story gains muscle."