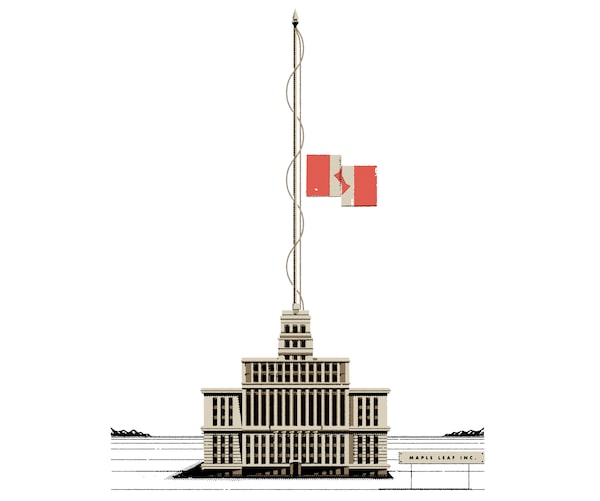

ILLUSTRATION BY MICHAEL HADDAD

Matthew J. Bellamy is an associate professor of history at Carleton University in Ottawa and the author of Profiting the Crown: Canada’s Polymer Corporation.

When General Motors announced in late November that it would be closing its plant in Oshawa, Ont., the outrage was immediate – and perfectly understandable. Here was a strategic move on the part of a multinational company, tearing out roots and slashing the manufacturing jobs that were the lifeblood of the town. Add in the billions of dollars that Ottawa had spent to keep the company in Canada, and it’s easy to see why Canadians would take this so personally.

Meanwhile, the recent news about Barrick Gold – that it would lay off more than half of the staff at its Toronto head office in the wake of a merger with Randgold, an African operator headquartered in the Channel Islands, and revamp its board of directors to leave just one Canadian-born member who lives in New York – hasn’t stirred the emotions in quite the same way. Fair enough, too: Much of Barrick’s business, since it transitioned from a money-losing oil and gas firm to a money-spinning mining company, has happened outside of Canada, in places such as the United States, Australia, the Dominican Republic, Peru, Argentina and Chile. And even though the company’s dynamic founder, Peter Munk, lived in Canada for seven decades, he passed away in March. Besides, even if industry veteran Pierre Lassonde says these recent moves effectively mean that Barrick is “not going to be a de facto Canadian company, period,” the company’s new chief executive, Mark Bristow, insists he plans to keep the headquarters in the city. So does it really matter that Barrick’s “heart” isn’t wrapped in red and white?

But Canada’s diminished presence in Barrick’s head office might actually be more lamentable, and a bigger blow to the national fabric. And the reasons go beyond Canadian culture’s usual inferiority complex, which gets inflamed when a homegrown kid leaves town.

The debate over what a Canadian company even is re-emerges virtually every time one gets taken over by a foreign firm. During the 1970s, when the “new nationalism” was on the rise in Canada, and roughly two-thirds of Canadians believed that the takeover of domestic firms – particularly by American ones – constituted a serious threat to our political and economic sovereignty, the federal government attempted to identify the elements that make up a “Canadian” corporation. It proved as problematic then as it does now. Was it the level of Canadian ownership, the number of Canadians in management or a mixture of both? And if so, how much of each? Did having two Canadian vice-presidents cancel out the one foreign-born president? That led to the 1973 Foreign Investment Review Act, which decided that a Canadian business was one “carried on in Canada by a Canadian corporation or an individual who is either a Canadian citizen or ordinarily resident in Canada, or by any combination in which one of such parties is in a position to control the conduct of the business.” It may be a bit of jargon-laden bafflegab, but it does at least signal Ottawa’s preference for keeping controlling interests – which usually lie with head offices – in the country.

Headquarters matter. They employ well-educated and highly skilled people including senior managers, accountants, financiers and human-resource specialists, and they generate jobs in ancillary services, too, from auditors to information technologists. Headquarters also act as a magnet for other companies, leading to industrial clusters that have had a profound effect on local identities. Just think of the clustering of banks in Toronto in the early 1900s; since that time and to this day, Toronto’s identity is defined, in part, by being the financial capital of Canada.

It’s why the Canadian government has historically been far more willing to allow takeovers when the conquering company promises to keep the head office in Canada. Take, for example, the Beijing-based China National Offshore Oil Corp.'s 2013 acquisition of the Calgary-headquartered energy producer Nexen Inc. After a long review, the federal government approved the US$15.1-billion deal because CNOOC made a series of undertakings to the Canadian government which included keeping its North American headquarters in Calgary.

But every time a company moves its head office from Canada, we lose revenue from corporate, income and excise taxes. Domestic suppliers go out of business, advertising agencies close and numerous spin-off industries disappear. Sometimes whole clusters go into decline.

The current state of Sarnia, Ont., shows what that scenario can look like. Polymer Corp., born on the shores of Lake Huron and out of the crucible of the Second World War, played a critical role in the Canadian economy for more than 50 years. Blending innovative science and technology with expert business and managerial strategies, the former Crown company kept Canada on the vanguard of international synthetic rubber developments, and Polymer became a symbol of our postwar industrial prowess. During the 1960s and 1970s, when Polymer was producing some of the best synthetic rubber in the world, there were more PhDs per capita in Sarnia than anywhere else in Canada. Scientists from all over the world came to work at Canadian companies on the cutting edge of technology, and so profitable was Polymer that the federal government even proudly placed an image of its Sarnia plant on the back of the $10 bill in 1971.

That prosperity is now in the past. In 1988, Alberta-based Nova Corp. bought Polymer, which had been renamed Polysar, and took it private, flipping it to German chemicals and health-care giant Bayer AG two years later. Bayer promised not to move the head office for three years, a promise it kept – before moving its headquarters to the United States. Sarnia became a blue-collar town, with a population that has declined nearly every year since the company’s HQ moved away, with declining population and projections of stalled growth, at best. The buzzing city core is no more.

Look, too, at what has happened to London, Ont., since Interbrew – which in 2008 became AB InBev when the Belgian brewer bought Anheuser-Busch for US$52-billion – purchased Labatt in 1995. Jobs have been lost, suppliers have gone out of business, and executives have moved to other places, taking their money and their talent to foreign destinations.

When head offices are built or relocate, it leads to a rise in the confidence in the new host community. By the early 2000s, Nortel and other tech companies inspired Canada’s sleepy capital to rebrand itself as cerebral, energetic and modern, with new headquarters set up almost every year in Ottawa between 1970 and the dot-com crash. These offices were the engines for generating community confidence and high-paying jobs, which spilled over into the local economy and civic culture. Roads were improved, the airport was renovated, new cosmopolitan restaurants opened and the Rideau Centre shopping mall was built; the city even got an NHL team. Its high-flying tech confidence was even awkwardly referenced into the city’s memorable, if short-lived, slogan: “Ottawa: Technically Beautiful.”

But the nation’s capital also shows us what happens when headquarters pack up and leave. During that heyday, more than one-third of the employees of the major fibre-optics maker JDS Fitel Inc. – 10,000 people – were employed in Ottawa. But after a merger with Uniphase Corp., JDS moved its headquarters to San Jose, Calif., in 2003, leaving the city as an outpost; within a year of the move, only around 500 people remained. Its departure, the acquisition of major Ottawa tech firms such as Jetform and Newbridge Networks, and the collapse of Nortel as a major entity led to the mantle of “Silicon Valley North” moving to other cities.

The United States knows these effects well, which is why the country has defined their terms and defended their turf. President Donald Trump has been urging American corporations to “come home,” and is calling for an end to the practice of “tax inversion” – whereby a U.S. company is acquired by a smaller foreign business from a low-tax country, adopts it as its domicile and reduces the combined firm’s overall U.S. tax burden. And when pollsters asked what characteristic most defines an “American company,” 75 per cent of Americans put “manufacturing its products in the United States” at the top of the list.

Barrick wouldn’t even rise to this definition in Canada. But that just means we need to raise our standards. For a country whose primary industries already tend to be dominated by foreign-owned companies in terms of employees and value – manufacturing, automotive, and finance and insurance – Canadians cannot be complacent.

This is not the rant of an old-school economic nationalist. These are not the last ravings of old-school economic nationalism, suffocated at last by neo-liberalism. This is a heartfelt lament. Because when Canadian companies move their headquarters out of the country, we lose not only revenue from taxes – but also a bit more of our Canadian culture.