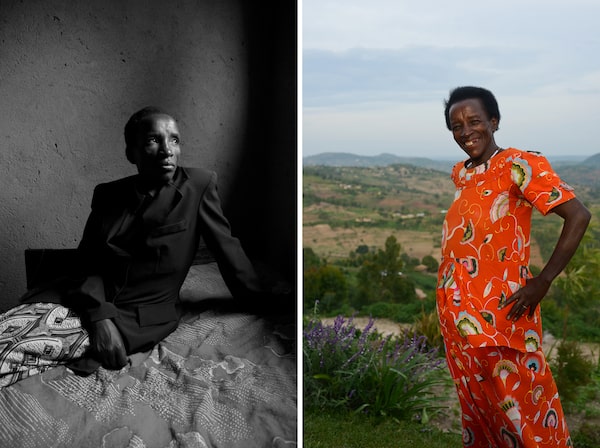

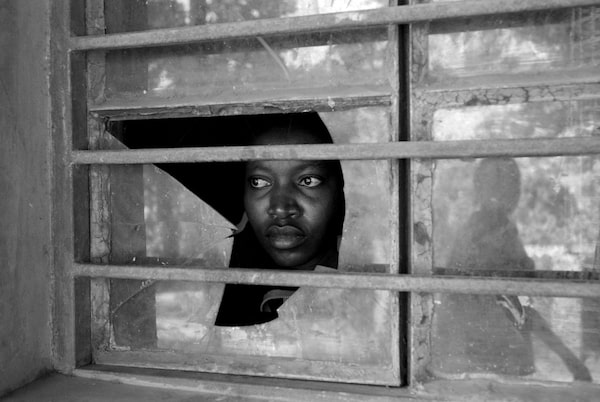

These six people are among the many resilient women who, 25 years after the Rwandan genocide, are profiled in a new book about survivors of the African nation's horrors. They are, clockwise from top left: Marie Louise, Marie, Pascasie, Mama Lambert, Gloriose and Hyacintha.Photography and story by Samer Muscati/Handout

Samer Muscati is a Canadian lawyer, documentary photographer and former journalist. As a senior researcher for Human Rights Watch, he focused on women’s rights in conflict zones. He runs the International Human Rights program at University of Toronto’s faculty of law. This project is a collaboration with Sandra Ka Hon Chu, director of research and advocacy at the Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network, where she works on HIV-related human-rights issues concerning prisons, drug policy, sex work, women and immigration.

An estimated 250,000 to 500,000 women were raped over 100 days during the 1994 genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda. No one was spared: Grandmothers were assaulted in the presence of their grandchildren; girls witnessed the massacre of their families before being abducted. As Rwanda commemorates 25 years since the onset of the genocide on April 7, 1994, much of the world’s attention will be focused on the senseless violence that devastated this African country as the international community stood passively by. While this commemoration is important, too often the stories we tell of genocide end with its horrific violence, forever framing its survivors as victims.

This April 7, there is another story that needs to be told.

Rwandans who endured the most ruthless acts of sexual violence imaginable have managed to not only survive, but to heal in the face of trauma, loss and poverty. Although the stains of the genocide are permanent, survivors illustrate the importance of international and domestic support during and after a conflict. This support has allowed survivors to access health care and socioeconomic support, including counselling, HIV treatment, housing and microcredit programs.

To document their remarkable journeys, our team returned to Rwanda in November, 2018, to interview and photograph survivors who had shared their testimonials with us 10 years earlier. We were struck by their transformation. Our new book showcases survivors’ extraordinary will, resilience and determination to make a better life for themselves and their children, in the face of seemingly irreparable harms. These women are an enduring testament to our collective abandonment of them. But they also represent the promise of transformative change.

Marie Louise

Marie Louise, shown with her children in 2008 (above) and 2018 (below).

Marie Louise, 43, was living with her family when the genocide began. As the violence spread, she sought shelter in a Catholic church, which swiftly became the site of a massacre. She miraculously survived after being left for dead among the bodies of others. After the génocidaires left, she hid for several days in bushes, but was eventually spotted by a soldier, who abducted and enslaved her in a house where he raped her repeatedly over five days. He was not the last.

“Before the genocide, I had never been intimate with a man, and yet now I have gotten to know many without my consent,” Marie Louise told us 10 years ago. Today, she is living with HIV as a result of the sexual violence, one of many Rwandan survivors who share this fate.

Support from the Rwandan government and international aid organizations has allowed Marie Louise to become self-sufficient; she now has a plot of land where she cultivates cassava and beans, and also owns a cow.

“Nothing gives me more joy than being a mother. Many women of my age died during the genocide, so I am so happy that I am still alive and even have children,” she told us last year. “When I look at my children, I see my family: my brothers, sisters, uncles. When I see them, I see my future ahead; because of them, I have hope.”

Marie

Marie, shown in her home in Rusatira in 2008 and in 2018.

Marie, 62, a Hutu woman, was targeted during the Rwandan genocide because her husband and children were Tutsi. Marie hid in the bush with her infant son, both surviving on wild fruit. An Interahamwe militia member discovered and raped Marie, who was pregnant with her fifth child. During those 100 days, other militia raped Marie and she contracted HIV.

“I want you to know that the horrors people inflicted during the genocide are more than any human being can endure,” she told us 10 years ago. “For a long time after, I despised myself for what had happened to me. I hated everything that surrounded me, because it reminded me of what I had lost.”

Today, Marie says she is doing much better after connecting with other survivors and getting counselling. She has joined other women to establish an agricultural co-operative to grow pineapples and fruit trees. “Before I shared my testimony a decade ago, I had no hope for the future. All I could think of was, 'How am I going to live?’ I did not want to say anything about what happened to me; my story was mine, and I did not see a need to share it. But when I finally found the courage to share my story, it went out into the world and that helped restore my hope. By speaking with counsellors, I began to deal with my trauma. I also connected with other genocide survivors of sexual violence. Until then, I thought that I was alone, but when I heard that others suffered the same problems that I faced, it touched my heart.”

Gloriose

Gloriose, 43, is shown in Kigali in 2008 (above) and 2018 (below).

Gloriose, 43, watched the Interahamwe stab and beat her father to death during the genocide. A priest tried to rescue Gloriose, her sister and some other children by hiding them in a classroom in a priests’ compound. After four days, the Interahamwe searched the compound and discovered them. This was the beginning of many horrible encounters. “One Interahamwe approached me and asked me to choose between life and death,” she told us 10 years ago. “I couldn’t answer him, so he tore my clothes off and ordered me to lie down. When I refused, one of the other militiamen hit me on the back with a nailed club. I fell and was bleeding heavily. This disgusted the Interahamwe who had wanted to rape me, so he left me there.”

After the genocide, Gloriose became homeless, wandering the streets, begging for food and doing odd jobs. Today, with support from non-governmental organizations, she has been able to rent a nice home, run a small business selling charcoal and pay for her children’s school materials and uniforms.

“I see a good future ahead for my children and me. If God keeps me alive, and if my children finish their studies and find a job, our lives will be good,” she told us last year. “Despite all that has happened to me, I will stand firm. I feel strong. I am a responsible woman and I will continue on the right track. I want to be a good example for others.”

Pascasie

Above, Pascasie sits in an unfinished Kigali church in 2008. Below, she shares her story at a group counselling session at Kigali's Solace Ministries in 2018.

When Pascasie, 60, thinks back to 1994, a feeling of coldness comes over her. She shivers when she recalls the freezing house where she was enslaved by a group of Interahamwe, wearing only her undergarments.

At the time of the genocide, Pascasie was visiting her parents in southern Rwanda. While fleeing the violence, Pascasie encountered groups of Interahamwe who raped her, confined her to a house and continued to violently assault her for two weeks. “They insulted and humiliated me. They told me that I was ugly and dirty and that I stank,” Pascasie told us 10 years ago. ”I was the only woman in the house, and for two weeks many Interahamwe raped me every day, using me as their personal sex slave.”

Today, Pascasie lives in a safe neighbourhood in a home provided by the Rwandan government and runs a small business delivering produce. Local and international organizations have also provided her with support. Pascasie wants the world to know that she has come a long way since the genocide, but that her trauma continues.

“Over all, I am doing fine, but I still cannot forget what happened to me during the genocide,” she told us last year. “Sometimes when I am alone, I think about all that I have suffered. I see it all playing in my mind like a movie. I do not think we will ever forget what happened; it will always come back. This is the life we must accept to live. We cannot forget; we just pretend not to remember.”

Hyacintha

Hyacintha, shown above in Kigali in 2008 and below outside Solace Ministries in 2018.

Hyacintha, 37, was only 12 when the genocide began. After a group of Interahamwe beat her father to death with a nailed club, Hyacintha’s family fled in different directions. Hyacintha following her older sister, and the two sought shelter with a Hutu classmate who raped both of them before Hyacintha managed to escape, only to be captured by a government soldier who kept her at his camp and raped her repeatedly over three months. Another soldier forced Hyacintha to be his “wife” even after the genocide ended, and for two years, Hyacintha endured his abuse. In January, 1997, she gave birth to a girl.

As Hyacintha shared with us 10 years ago: “I was only 12 years old when I was brutally raped during the genocide, at different times by different men. … I became a woman without even having a chance to be a girl. I did not know anything about sex; my parents never explained anything to me. I was not prepared to become a mother and take care of a baby.”

These days, Hyacintha says she feels empowered because of the support she has received. She owns cattle and has been able to grow crops that she sells at the market. She also runs her own small business making and selling banana juice.

Hyacintha told us last year, “As for forgiveness, I still feel that I cannot forgive the killers, rapists and looters of the genocide. I do not think you can simply forgive someone who has never come before you to ask for forgiveness. I cannot forgive someone who cannot even accept what he has done.”

Mama Lambert

Above, Mama Lambert stands in front of a genocide memorial outside Nyanza, where members of her family are buried, in 2008. Below, she embraces a woman at a Solace Ministries counselling session.

During the genocide, almost all of Beata’s family were murdered. She lost her husband, five of her eight children and other family members. Since the genocide, everyone knows her as “Mama Lambert,” the mother of Lambert, the infant boy she carried on her back while hiding from génocidaires during those horrible 100 days.

She has forgiven the murderers of her family. Mama Lambert is now a counsellor with Solace Ministries in Rwanda, an organization that supports thousands of genocide survivors, including those featured here. She continues to be a source of comfort and inspiration for many fellow survivors.

“In our culture, talking about sex is very private. That is why it was very hard for survivors to come up and reveal that they were raped. Some even killed themselves following the genocide. But nowadays things are changing slowly,” she told us last year. “We believe that we should not keep quiet; we should speak the truth so that justice could take its course. If you speak out, it can be a lesson to others. When you release your burden, you release your heart.”

Samer Muscati and Sandra Ka Hon Chu are co-editors of the book and photography exhibition And I Live On: The Resilience of Rwandan Genocide Survivors of Sexual Violence, on display at the University of Toronto’s Hart House until May 31.