It's easy to get lost on the forested campus of Wellesley College, the private all-women's university a half-hour away from Boston. The blue dot on your phone's GPS is too small and the light thrown by the storybook lampposts too dim for a New England night in the fog of December. A quiet university campus at 11 p.m. is not the most comfortable place for a woman to walk alone, and so at first, you let the stranger behind you move ahead. But very quickly, perhaps after the third or fourth person has walked on by, you notice that they are all women. They feel safe here and so you do, too.

For the century and a half of its existence, Wellesley College has allowed its female students to experience that safety not for one or two nights but for every night of the four years they spend at the college.

The safety isn't merely physical. Wellesley is a place where, students will tell you, they feel liberated from the constraints that, as women, they take for granted in the outside world. In one student's words, the place is "an incubator to learn and grow and change … a good bubble." It's also a powerful alumnae network – graduates talk about turning to other Wellesley women for advice, not just on careers, but on every stage of life: marriage, children, aging parents.

"It's kind of like a football team; you are always rooting for everyone," says Shelly Anand, a co-founder of the online magazine for alumni, Wellesley Underground, and a lawyer in Atlanta. "You come out with a unique mindset and a unique new voice."

On Nov. 8, it seemed as if the school would celebrate the most high-profile success in its history: the ascendance to the presidency of Hillary Clinton, Class of 1969.

Thousands of alumnae had travelled to attend an official election-night watch party. Party favours included specially commissioned little wooden hammers with the stamped motto "Wellesley women break glass ceilings" and cupcakes decorated with shards of broken glass made from melted sugar.

"It turned quite dark and poignant over the course of the evening," recalls Rose Whitlock, a member of Feminists for Reproductive Justice (affiliated with Planned Parenthood) and a founding editor of campus literary magazine, The Lamppost.

During the campaign, it had been easy to believe that opposition to Trump would unite women, even Republicans. Many pundits, in fact, made exactly that assumption. In October, superstar pollster Nate Silver declared that "Women are Defeating Donald Trump."

But Mr. Silver was wrong.

For many women, gender was not the central issue.

On election night, as Wellesley College was processing the failure of a woman many consider their role model, 700 kilometres away, Kylie Thomas was rejoicing. Ms. Thomas founded a Women for Trump chapter at Pennsylvania State University, a publicly funded school.

She is also a committed Republican who never considered voting for Hillary Clinton. She reviles her.

She mentions Benghazi, the Wikileaks e-mail imbroglio, the increase in mass incarceration during Bill Clinton's time in office (the last an issue frequently cited by Democratic supporters who were skeptical of Ms. Clinton's run).

"Hillary had blood on her hands and Donald Trump didn't. There are lives that are gone, there are families that are broken up because of Hillary Clinton," Ms. Thomas says.

The Republican Party is not flawless, in her view – it's too "old" – but Ms. Thomas plans to change it from the inside, part of a millennial wave she hopes will sweep clean the establishment. She will be applying to law school, then clerk for a Supreme Court judge, run for office.

The tragedy felt at Wellesley, a liberal Seven Sisters college, was not a tragedy for all womankind. For every female student who subscribes to feminism's intersectional third wave, there are women who belong to the Network of Enlightened Women, a conservative national group, for whom terms such as "intersectional" and "third-wave" have little resonance.

Her own university remained a dot of blue in a state that was painted almost entirely red, but there was support for Trump at Penn State as well.

"College campuses want everyone to look different, but they want everyone to think the same," says Ms. Thomas. "We can't. We were raised in different places and by different people."

Over the course of two weeks, The Globe and Mail travelled to Penn State and Wellesley, taking the measure of these differences at the two universities, and speaking to students and professors at other American colleges as well. As with so many political movements, the discussion over gender in the American election feels most urgent on campus.

With a female candidate in the running, this election couldn't help but foreground the issue of feminism in America. The election result revealed that feminism is a movement that does not move all women. Even as next week's Women's March on Washington is billed as a march of solidarity to protest the election result and protect women's rights and health, it cannot efface the reality that feminism is at a crossroads. What role feminism will play in the lives of women who are now launching their lives is up for debate.

At Wellesley, the epicentre of young, liberal self-described feminists, there are fevered questions about how to reach outside its bubble to talk to women across the political spectrum. It's not clear what the conversation would be about. Female supporters for Trump see their candidate's victory as a moment when their personal ambition is matched by the country's political realities.

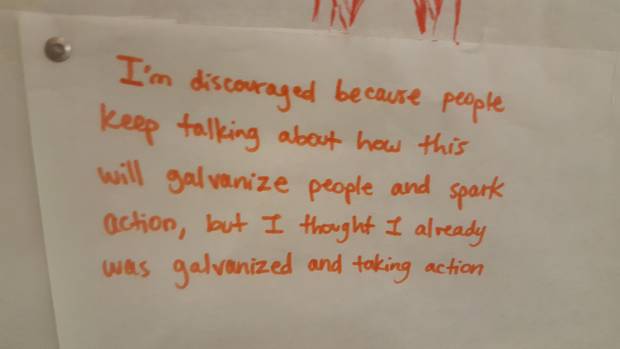

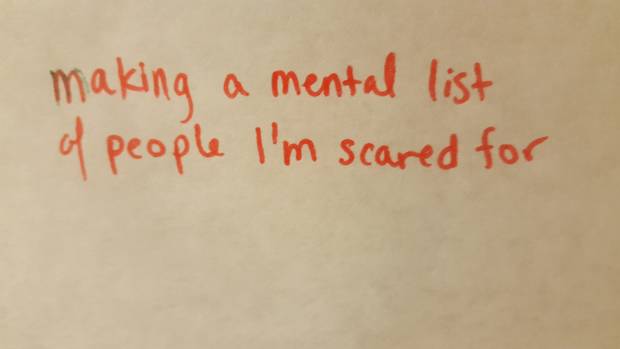

These are some of the messages patrons at El Table left about the 2016 election, which many students at the private all-women’s college said was the saddest day in their lives.

'A fresh face to the Republican party'

"I think a lot of people felt the vote by women was more surprising because of how Trump behaved [during his campaign]," says Melissa Deckman, a political-science professor at Washington College, who studies conservative female political movements. When, in fact, "the vote by women was not remarkably different than in elections over the last 20 years."

White, college-educated Republican women voted for Mr. Trump in numbers that dipped only slightly from the support enjoyed by Mitt Romney in 2012.

Dr. Deckman, the author of Tea Party Women: Mama Grizzlies, Grassroots Leaders and the Changing Face of the American Right, says the vote showed much of what her research had already found about right-wing women of all ages: They are a rising political force, but feminism is secondary to their concerns.

"There is resentment among conservative women that they should be pro-choice, that they should embrace feminism. … Feminism is not a priority for them," she says.

Ms. Thomas at Penn State would agree. She is part of a small but growing group of young women who are raising conservative voices. When we meet, she is wearing a T-shirt that says "Adorable Deplorable" – a nod to Ms. Clinton's characterization of Trump supporters – and tells me she also has another one that features an elephant wearing Mr. Trump's hair.

"The new right is people like me," she says. "We try to use humour to keep people interested and engaged. We bring a fresh face to the Republican party. If you look at the Republican party, they are a bunch of old people," she says.

Mr. Trump is no young man, and he was not Ms. Thomas's first choice. She would have preferred Ben Carson. But what resonated with her, as with every young Trump supporter whom The Globe interviewed, was Mr. Trump's promise to deport illegal and undocumented immigrants. Undocumented immigrants receive scarce public resources to which they are not entitled, she and other Trump supporters argue.

For her, Mr. Trump's promise to build a wall between America and Mexico had far deeper resonance than his misogynist comments.

"When the entire thing came out with Trump and his vulgar words, everyone was scared to say that they supported him. … They thought that supporting him was condoning what he said. I don't condone what he said, but that was over a decade ago," she says.

When I ask what feminism means to her, the ambitious Ms. Thomas takes a deep breath and says she is a first– or second-wave feminist, not a third-wave one.

"I don't too much believe in a gender gap, but without the precedents that have been set forward [in feminism], we would not be where we are now," she says. She believes in equality of opportunity, but not affirmative action.

"The third-wave movements are demanding, instead of asking: 'What can I accomplish?' "

I tell her that I will soon be heading to Wellesley, where I will likely meet lots of third-wavers. Does she have any questions for them?

"What would it take for Americans to be united now that the election is over?" she says. "That's what I want to ask them."

Racial fractures, and economic divides

Finding unity among women is complicated by cultural divisions along other lines. Having a dialogue across certain chasms – economic, racial – isn't as simple as it may seem.

Jalena Keane-Lee, a Wellesley major in cinema and media studies and political science, says it is not up to her, a woman of colour, to put herself out there to educate a possibly racist Trump voter.

"People of colour should not have to walk into a room and explain our own humanity," she says.

Her mission at the moment, she says, is to protect the vulnerable, to #resist, as the Twitter campaign would have it. On Jan. 21, she will be at the march with her mother and her sister.

"If you were waiting for a time to get involved with political action, you can't wait any more," she says.

The role of race has been an issue for the Women's March as well, with organizers initially arguing over whether its first name – "the Million Women March" – was appropriating a 1997 protest by African-American women.

Feminism must focus on race, Ms. Keane-Lee says. "Who you define as a woman is really interesting. The first and second wave of feminism were defining women as white women. With the third wave, people are trying to push back. You can't have feminism if you don't fight for racial equality, if you don't fight for socioeconomic equality."

The job of talking to the other side might be one for a white ally, she suggests.

That could be Ismar Volic.

Dr. Volic has been teaching math at Wellesley College for over a decade. He, too, is troubled by the recent tenor of politics in the United States, and blames an economic divide for contributing to the rise of the right.

Dr. Volic now desperately wants to find a way to help his students break out of what he sees as a Wellesley bubble. "The thing I worry about is the isolationist aspect of things. A lot of our students have been funnelled through an educational path that is fairly elite; and fairly closed, elite colleges like Wellesley, that are bubbles unto themselves, are not doing enough to bridge these gaps which are now so evident and shocking to all of us," he says.

But some of his students disagree with him. As we chat at the end of one of his classes, four of them make their case.

Their lives once they leave this campus, they point out, are lived outside any bubble. Many come from Republican families. One talks about a Thanksgiving visit that ended with a slammed door and an early departure. Another mentions calling home to speak to an ill relative and being berated for not supporting Mr. Trump. Others did not go home at all, pleading due dates for papers.

Even assuming that their enrolment here is a reflection of their privilege can be a mistake, they say. Almost a sixth of students at Wellesley are the first in their family to go to university; 60 per cent receive financial aid.

Wellesley is not so much a bubble which protects them, they say, as one where they have a moment to find themselves. And it's a place they learn to fight.

"Especially entering into a mostly male environment, it's incredibly useful to have a background that acts as if there is no patriarchy," says Caroline Bechtel, a senior who is also a cadet in the Reserve Officers' Training Corps. When she graduates this spring, she will take up her first full-time posting, in Hawaii.

"When I am going out and leading a group of all guys, I know that there may be systemic biases in place, but I am ready to navigate those situations. If someone tried to mansplain me, I check it on the spot: 'Hey, I'm talking here.' You address it the same way a man would address it."

If there is a bubble at Wellesley, it is a political one, most agree.

Ms. Bechtel, who is from Indiana, says she hopes her friends at Wellesley will not dismiss the part of the United States that they call "flyover country."

"I am so afraid that my Wellesley classmates are not going to talk to anyone, because when I think about what changed my world view – like Hillary, I was a Republican in high school – is that people were willing to talk to me and not call me racist if I didn't know the difference between Latino and Hispanic," she says.

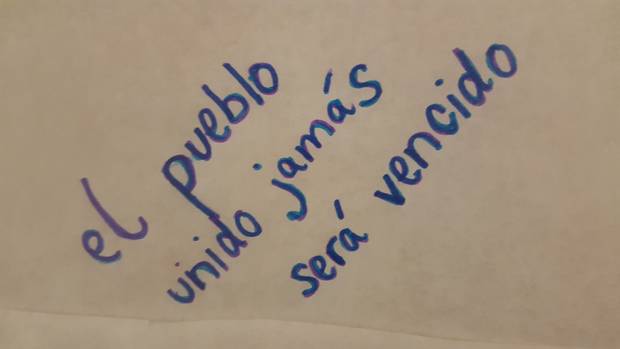

On the wall at El Table, one message in Spanish reads: ‘The people united will never be defeated.’

Crossing divides, one feminist at a time

Perhaps the most powerful analytical tool that feminism offers is that of measuring the small, personal experience against the political – discovering where it rings untrue, where it falls short, where it matches. It's something that professors at Wellesley teach.

"There is a reason that the phrase 'the personal is political' has remained so cognizant and so important," says Irene Mata, an associate professor of women's and gender studies. "If you are in a classroom and you are having really complicated discussions about race or really difficult discussions around class privilege or first-generation students, you may not understand that experience. If we are going to challenge how we see the world, we have to challenge our experience in the world."

Personal experience might not be a lot to hang a dialogue on, but it could be a start.

One evening at Wellesley I find myself listening to a couple of dozen women attend a meeting of the College Democrats.

They are here to ask questions of Sonia Chang-Diaz, a thirtysomething Massachusetts state representative, and the first Latina elected to that state's senate. It's a discussion about who they are now, who they might be in the future, how they will get there, if they can get there.

How do you balance motherhood and politics? Did you face challenges as a woman of colour? What is one of your key battles?

With many answers, Ms. Chang-Diaz refers to her work across party lines. She co-ordinated with Republican women to find space and time to nurse at work; she's trying to champion early-childhood education by building a non-partisan alliance.

The young female supporters for Mr. Trump I speak to all have friends who are Democrats.

On election night, Ms. Thomas spent part of her evening with a close friend who campaigned for Ms. Clinton. They had met when Ms. Thomas approached her in the spring when they were staffing campaign tables across from each other.

"I asked her why she supported Hillary. She got her back up so hard-core," Ms. Thomas says. "On election day, she had a 'Stronger Together' sign and I had my Trump gear and we were together. People thought we were a joke."

What seemed like a joke could be closer to the future of feminism than many may now guess.

Simona Chiose is The Globe and Mail's higher-education reporter. Follow her on Twitter: @srchiose

SNAPSHOTS OF AMERICA: MORE FROM THE GLOBE AND MAIL

Want to spend a night at Trump’s Mar-a-Lago resort? It’ll cost you