Since 2012, Megan Adams has been plunging into the Great Bear rain forest of central British Columbia by truck, boat and helicopter, looking for suitable places to string up a roll of 15.5-gauge barbed wire to snag tufts of hair from passing black and grizzly bears.

Five years and more than a kilometre-worth of wire later, the wildlife ecologist has collected hundreds of hair samples which, when combined with hundreds more from across the province, reveal in greater detail than ever before one of the most important predator-prey relationships in North America and an underappreciated link between land and sea.

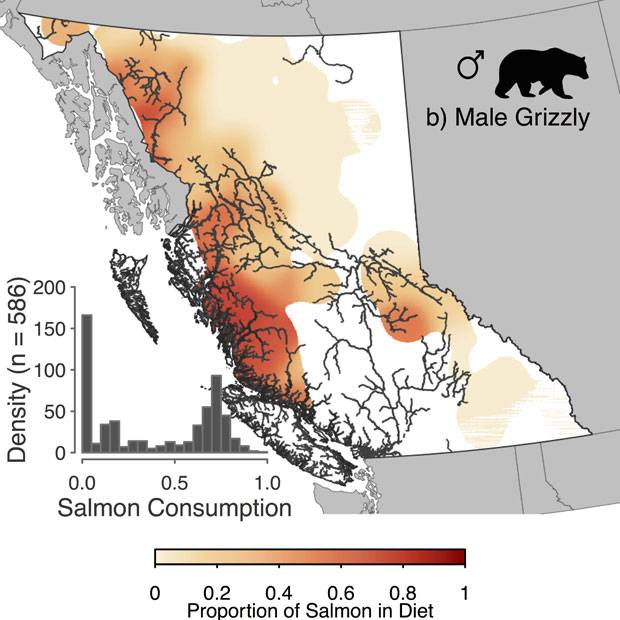

The result, published this week in the open access journal Ecosphere, shows the extent to which bears in B.C. are acquiring nutrients from the open ocean though eating salmon. In some cases, those nutrients are finding their way many hundreds of kilometres inland, forming "hot spots" near the Alberta border where bears are thriving on a high salmon diet.

"We know the 'fishiest' bears are the healthiest bears," said Ms. Adams, a wildlife ecologist and PhD student at the University of Victoria. "We wanted to know where those bears live."

While it's no surprise that bears eat salmon, the study quantifies that relationship with a series of detailed maps that span the entire province. The maps show important differences between the diets of different bear species and between males and females. The data are presented at a regional scale that can inform conservation practices and illuminate the degree to which bears should be factored into decisions regarding the salmon fishery.

In this map, researchers show salmon consumption among male grizzly bears in British Columbia. Darker areas correspond to greater reliance on salmon while the grey lines denote major salmon-bearing rivers.The bar graph at lower left shows how much salmon the 586 mail grizzly bears eat, with those further to the right showing increasingly higher salmon consumption.

"It's a striking reminder of the need to re-examine the way marine resources are managed with terrestrial users in mind," said Chris Darimont, the senior author on the study, who heads the university's Hakai-Raincoast applied-conservation lab, based in Victoria.

Dr. Darimont added that federal and provincial governments have historically separated the way ocean and land-based resources and ecosystems are managed in a way that does not reflect the deep biological connection between the two.

Nine scientists were involved in the work – including Dr. Darimont and Ms. Adams – which was supported by the Sidney, B.C.-based Raincoast Conservation Foundation and conducted in collaboration with the Wuikinuxv First Nation. The study is part of a larger effort by coastal First Nations groups to better characterize the behaviour and health of bear populations in their territory in response to those who dismiss the value of traditional knowledge about the animals.

"We're empowering ourselves by reaching out and getting the science that is so desperately needed in order to help the wildlife," said Danielle Shaw, who is stewardship director for the Wuikinuxv Nation, in Rivers Inlet, B.C. The community's interest in bears includes opposition to the controversial practice of trophy hunting, which the province allows but which could change depending on the fallout from the recent, tightly-contested provincial election.

Reviewing samples of the bears’ hair in a laboratory, Megan Adams and the researchers were able to learn more about the animals’ diet.

A.S. WRIGHT

The salmon study does not directly speak to trophy hunting but offers information about the health of bear populations in different parts of the province based on an analysis of 1,400 hair samples. Ms. Adams and her colleagues measured isotopes of carbon and nitrogen in each of the samples to tease out details about the amount of animal protein in the bears' diets and measure the fraction of that protein that originates in the ocean. In particular, the isotope nitrogen-15 is more concentrated in ocean plankton than in terrestrial plants and makes its way up the marine food chain, eventually turning up as a reliable marker for salmon consumption in bear hair.

In keeping with earlier work by provincial scientists, Ms. Adams's study demonstrated that grizzly bears dominate the salmon resource and effectively outcompete their smaller black-bear cousins. Male grizzlies are the most pronounced salmon eaters.

"A number of the results are what we would have expected but she showed them in much finer detail," said Garth Mowat, a biologist and head of the province's natural resources science section, who provided Ms. Adams with access to more than two decade's worth of hair samples that the province has collected.

The researchers hope their study of the bears’ diet can guide effective conservation and fishery policies.

A.S. WRIGHT

The maps also show blank regions where salmon are abundant but where bears have largely been eliminated, or areas, such as the part of the Columbia River system that lies in Canada, where dams have prevented salmon from reaching far inland. Ms. Adams said the blank areas emphasize the need to protect those places where bears are still living well on salmon – a relationship that has important consequences for many other species in the food chain that scavenge the fish remains the bears discard.

She said she and her colleagues are now trying to combine what they have learned about salmon availability and human impacts. "We're just trying to find the fulcrums that determine if a bear is vulnerable or not to being excluded from salmon," she said.

Dr. Mowat said that the maps produced for the study would be useful for informing regional decision makers on matters of land use, habitat enhancement or human presence on the landscape.

"They are especially helpful for people who are not part of the science community … and hopefully will help them make better decisions," he said.

THE GLOBE ON SCIENCE: MORE FROM IVAN SEMENIUK