In the end, it was the human weaknesses that proved the undoing of the world's oldest dictator. Arrogance, pride, stubbornness and obsessive family loyalty – a mundane collection of ordinary frailties, but they were enough to bring down a ruler who had dominated Zimbabwe for 37 years.

The signs of a looming military coup must have been obvious to Robert Mugabe. His top generals were against his plan to give a senior government post to his unpopular wife, Grace. The once-petty feud between her and the commanders was growing increasingly bitter, and she was insulting and mocking the military men and their political allies.

Mr. Mugabe controlled a vast security apparatus, including a secret police agency that would have certainly told him of the warning signs from the army.

Yet he didn't even need an intelligence report. By early this week, the likelihood of a military intervention was a secret to nobody. Senior military officers called a press conference, issued a public threat to the Mugabe regime, and announced that they might need to step in. The ruling party responded with nothing more than a haughty verbal reprimand.

Two days later, the army commanders launched their takeover. But even when the armoured vehicles were rolling into Harare, the President did nothing.

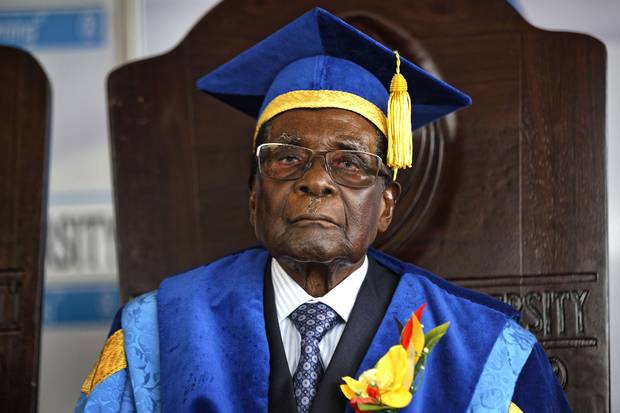

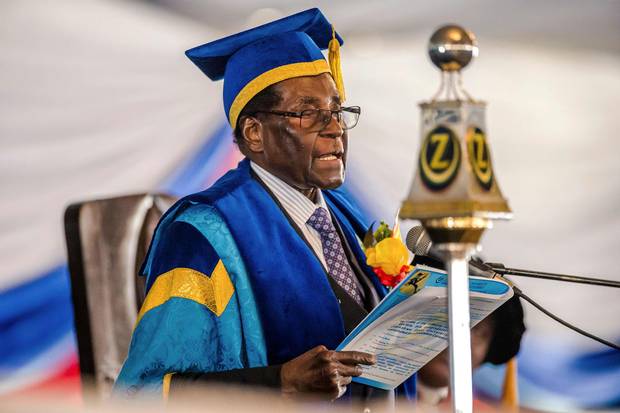

Why did the dictator fail to act? At the age of 93, while his health was declining and he needed help to walk to a podium, he was still alert and lucid. But he ignored the alarm bells from the Zimbabwean military and the Zimbabwean people. He was convinced of his popularity, believing in the results of rigged elections, without realizing that his authority was hollow and crumbling.

Zimbabweans who have watched him for decades have little doubt that it was Mr. Mugabe's own imperious egotism that led to his downfall. He saw the danger signs, yet his supreme confidence led him to assume that he could swat away the threats with yet another sacking or another arrest.

"Big people tend to over-reach, and he over-reached himself," says Earnest Mudzengi, a political analyst in Harare.

"His system had collapsed around him. Surely he should have known. It's a sad end for him. He led a guerrilla warfare in the 1970s, the people looked up to him – and now they're chasing him away."

Tendai Biti, a former finance minister who worked with Mr. Mugabe in government from 2009 to 2013, says the autocrat was destroyed by his own pride. "Hubristic arrogance," he told The Globe and Mail. "He was in power so long. He became so comfortable, complacent and over-confident. He's stubborn, and he forgot the nature of the state around him. This is a military state, a state of securocrats. He forgot that he was just a representative of a securocratic state, and it will always dump you if you don't serve it. So they fired him."

Nov. 15: A youth washes a minibus bearing Mr. Mugabe’s portrait at a bus terminal in Harare.

PHILIMON BULAWAYO/REUTERS

Nov. 15, 2017: Soldiers stand on the streets in Harare after the military’s takeover.

PHILIMON BULAWAYO/REUTERS

Nov. 15: An image from the Twitter account of Fadzayi Mahere, advocate of the High Court and Supreme Court of Zimbabwe, appears to show officers sitting in a line with troops guarding them in Harare.

AFP/GETTY IMAGES

MALAWI

ZAMBIA

Harare

ZIMBABWE

MOZAMBIQUE

BOTSWANA

SOUTH

AFRICA

0

200

KM

THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: MAPZEN; OSM;

NATURAL EARTH; WHO’S ON FIRST

MALAWI

ZAMBIA

Harare

ZIMBABWE

MOZAMBIQUE

BOTSWANA

SOUTH

AFRICA

0

200

KM

THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: MAPZEN; OSM;

NATURAL EARTH; WHO’S ON FIRST

MALAWI

ZAMBIA

Harare

ZIMBABWE

MOZAMBIQUE

BOTSWANA

SOUTH

AFRICA

0

200

KM

THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: MAPZEN; OSM; NATURAL EARTH; WHO’S ON FIRST

Grace under fire

For decades, Mr. Mugabe had shrewdly balanced the factions around him. He kept his enemies close. He used selective repression to weaken any camp that became too strong. Nobody was allowed to become the heir apparent.

But in recent years this strategy became cruder, less cautious and more impulsive. He decided that Ms. Mugabe must have her future guaranteed, and the only way to safeguard her ambitions was to give her a powerful government post: vice-president or perhaps even the coveted role of his official successor.

And to do that, he disrupted the delicate balance around him. After relying on military support for nearly four decades, he suddenly began to threaten the senior military officers, and they responded in a predictable way: by plotting against him.

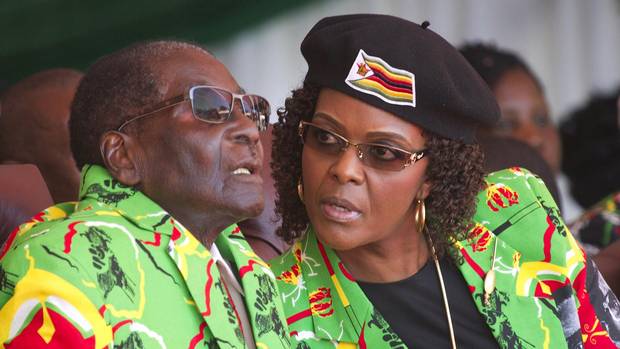

For most of their marriage, Grace Mugabe had stayed out of politics. More than 40 years younger than her husband, she was content to go on shopping sprees in Paris and Hong Kong, running several private businesses and enjoying the perks and wealth that flowed from her husband's power.

But everything changed after the 2013 election. It was blatantly rigged. The main opposition party, which had held a number of cabinet posts in a coalition government for the previous four years, was thrown into the political wilderness. With the regime's power now assured, the biggest remaining political question was the post-Mugabe succession within the ruling party itself.

Mr. Mugabe, left, and his wife Grace, shown in 2008.

ASSOCIATED PRESS

In 2014, as Mr. Mugabe's health deteriorated, the jostling and political tensions were becoming more visible. It became clear to Ms. Mugabe that she could lose everything if her husband died. She needed to secure her future. She felt the resentment of the older generation of politicians who gained their authority because they were veterans of the liberation war against white minority rule in the 1970s. If this veteran generation controlled the post-Mugabe succession, she could be stripped of her wealth and forced into exile.

Ms. Mugabe, leaping into the political arena, decided to ally herself with a younger generation of politicians, who became known as the G40 faction (Generation 40). Among them were several ambitious cabinet ministers who sought to bypass the war veterans and gain power after Mr. Mugabe's demise.

Grace Mugabe's first major move was to launch a nasty verbal campaign against Vice-President Joice Mujuru, a respected war veteran. Ms. Mugabe held a series of political rallies, whipping up hatred against Ms. Mujuru. It was a successful campaign: the Vice-President was fired at the end of 2014.

Joice Mujuru.

AFP/GETTY IMAGES

Ms. Mujuru was replaced by another war veteran, Emmerson Mnangagwa, who had been a crucial ally of Mr. Mugabe since the guerrilla war of the 1970s. As the security minister in the Mugabe cabinet, he led a bloody crackdown on dissidents in the Matabeleland region in the 1980s, and continued to play a key role in supporting Mr. Mugabe in other crises, including the 2008 election when the ruling party was on the verge of losing power.

Emmerson Mnangagwa.

JEKESAI NJIKIZANA/AFP/GETTY IMAGES

It was obvious to Ms. Mugabe that Mr. Mnangagwa posed a serious threat to her ambitions. She turned against him, spearheading another furious campaign of political rallies and crude insults. "The snake must be hit on the head," she declared.

She also attacked his military allies – including the army commander, General Constantino Chiwenga, another liberation war veteran. There were growing reports that Mr. Mugabe would conduct a sweeping purge of the highest levels of the military ranks to ensure that the army was neutralized.

The factional conflict, by now, was becoming so intense that Ms. Mugabe heard scattered jeers from Mr. Mnangagwa's supporters at one of her rallies. She ramped up the pressure on her husband to take action against her foes. The ruling party announced a special congress for December, where Ms. Mugabe and her supporters could be appointed to key positions.

On Nov. 6, the President fired Mr. Mnangagwa for "disloyalty, disrespect, deceitfulness and unreliability." But in a crucial error, Mr. Mugabe's police and security agents failed to prevent Mr. Mnangagwa from slipping out of the country, where he was able to mobilize support and issue a taunting statement.

General Chiwenga, meanwhile, was on an official visit to China. When he returned to Zimbabwe last weekend, there was reportedly an attempt to arrest him – but he had arranged to protect himself with a military unit at the airport, and the police were unable to seize him.

On Monday, he made an extraordinary appearance before the television cameras, backed up by almost every senior military commander in the country. It was a remarkable moment: the top military chief was publicly criticizing the Mugabe government in harsh and bitter words, while openly threatening that the military could intervene. With hindsight, his words were a clear guide to the army's plans to target Ms. Mugabe and the G40 faction – yet Mr. Mugabe failed to take any steps to halt him.

Nov. 13: General Constantino Chiwenga addresses a news conference held at the Zimbabwean Army Headquarters in Harare.

JEKESAI NJIKIZANA/AFP/GETTY IMAGES

While he did not name Ms. Mugabe or her G40 allies, General Chiwenga was unmistakably referring to them. He painted them as a generation too young to have legitimacy in Zimbabwe. "The history of our revolution cannot be rewritten by those who have not been part of it," he said.

"It is saddening to see our revolution being hijacked…. We must remind those behind the current treacherous shenanigans that when it comes to matters of protecting our revolution, the military will not hesitate to step in."

Mr. Mugabe ruling party, ZANU-PF, issued a brief statement to denounce General Chiwenga's comments, but its rebuke was brushed aside. Two days after the commander's warning, the military did exactly what it said it would do.

Nov. 15: Major-General Sibusiso Moyo reading a statement on television announcing the military takeover.

DEWA MAVHINGADEWA/AFP/GETTY IMAGES

Armoured vehicles rumbled out of a military base and rolled into Harare, taking control of all key sites. Mr. Mugabe was placed under military guard in his home, permitted to leave only under military escort. Several leading members of the G40 faction, including several cabinet ministers, were arrested and taken to military barracks.

As for Ms. Mugabe herself: She vanished from public view, her whereabouts unknown, although some reports suggested that she was holed up in the presidential residence.

While the details of Mr. Mugabe's exit were still being negotiated on Friday, it was the end of the Mugabe era.

Invincible no more

There was a time in Zimbabwe when Robert Mugabe was popular. As the leader of the main guerrilla movement that had fought white-minority rule, he swept to power in a landslide victory in the 1980 election. He outmanoeuvred every other politician, eliminating every threat from rival guerrilla leaders such as Joshua Nkomo.

But his economic mismanagement – seizing farmland, imposing state controls, fuelling inflation, destroying the industrial sector – led to widespread poverty and unemployment, which in turn eroded his popularity. Hyperinflation erupted in 2008, and the national GDP collapsed. Only a military crackdown saved him from a looming defeat in the 2008 election.

After a brief recovery under the coalition government from 2009 to 2013, the economy fell into decline again. Sporadic cash shortages and commodity shortages led to panic buying and rising economic anxieties.

In 1980, when Mr. Mugabe won his first election, Zimbabwe's economy was twice as large as that of neighbouring Zambia, and its average incomes were higher than those in most countries in southern Africa. Today its economy is smaller than Zambia's, and its life expectancy is lower than it was in 1980.

Last Monday, in his pre-coup statement, General Chiwenga cited the deteriorating economy as one of the main reasons for his potential intervention. He made it clear that the economy has tumbled into decline since the end of the coalition government in 2013.

"As a result of squabbling within the ranks of ZANU-PF, there has been no meaningful development in the country for the past five years," he said. "The resultant economic impasse has ushered in more challenges to the Zimbabwean populace, such as cash shortages and rising commodity prices."

It is the battered economy, more than anything else, that has created public support for the military coup. Zimbabweans are not enthusiastic supporters of the army, especially after its human-rights abuses in the past, but the army's promises have provided a glimmer of hope. So when the military seized power and put Mr. Mugabe under house arrest, there was no outpouring of support for the elderly leader. Nobody bothered to defend him.

"People have been heartily sick of Mugabe for a long time, and Grace has done him no favours with her rude behaviour," said David Moore, a Canadian scholar and Zimbabwe expert at the University of Johannesburg.

Nov. 16: A man has a shave at a street barber, next to a covered poster of Mr. Mugabe, in the low-income neighbourhood of Mbare in Harare.

BEN CURTIS/ASSOCIATED PRESS

Interviews in Harare confirm that the coup was widely supported. Tinaye Gomo, who scrounges a meagre living by selling pirated music discs on the streets of Harare, was quick to welcome the intervention. "Things were very bad," he said this week, a day after the military intervention. "There is nothing at home, so I have to work very late at night. But now things are getting better. We're very happy."

Vivid Gwede, an independent political analyst and human rights activist in Harare, says the Zimbabwean people felt a yearning for any kind of new regime after so many years of Mugabe rule. "People are desperate for change," he says. "For a lot of people here, any kind of change is a good thing. For 37 years, they've been under one leader whose rule was dictatorial, and they've suffered a lot of economic victimization. Elections haven't worked, demonstrations are violently suppressed, and people feel under siege."

Mr. Mugabe's own blunders led to his fall, Mr. Gwede says. "When someone is in power for 37 years, there is the myth of invincibility. And Mugabe himself believed it. He forgot that his rule was based on the security agencies, not the popular will. He showed arrogance, and the military decided that enough was enough. He was aware that something was afoot, but he couldn't stop it."

One of his biggest blunders was to allow his politically inexperienced wife to share his power. "She has an inflated sense of superiority, but she lacks the emotional intelligence to know that you shouldn't insult people in public," Mr. Gwede says. "She seems to revel in the limelight."

Ms. Mugabe and the G40 faction made another political error by pushing for a swift entrenchment of their power at the special ZANU-PF conference next month.

"I think G40 tried to move too fast to get their slate set for the December conference," Mr. Moore says. "They figured they'd have to work fast to get their slate in, but their hubris made them move too fast, and they underestimated the savvy of their enemy. And they have no guns. Without guns they had no chance."

Nov. 16: A man walks past a military tank parked on the side of a Harare street.

AFP/GETTY IMAGES

In the end, Mr. Mugabe became a victim of his own willingness to encourage the military to intervene in political issues – a pattern that continued from the army massacres in Matabeleland in the 1980s to the blatant military interference in the 2008 election. "He promoted military intervention in civilian affairs, and this was a direct result of that," Mr. Gwede says. "His grip on the army began loosening last year, and then he complained of military intervention in the political succession battle."

The military coup was carefully planned and shrewdly organized, with a minimum of disruption. Mr. Biti, the former finance minister, says the army commanders avoided the three biggest mistakes of most coups: they did not inflict great bloodshed, they did not disrupt the lives of ordinary people, and they did not wreak revenge on their enemies.

As a result, they have retained a significant amount of public support, and they still have a chance to gain legitimacy for their intervention by persuading ZANU-PF to drop Mr. Mugabe as the party's leader – allowing the military to maintain the fiction that this was not a coup.

"The army wants a soft landing for Robert Mugabe, because they respect him," Mr. Mudzengi says. "They are the same guys as him. He made those guys, and they made him."

Mr. Mugabe, true to his character, stubbornly refused to resign when the generals took over. But the military has continued to play the game shrewdly, allowing him to keep his dignity. On Thursday, it permitted him to be photographed at a negotiating session with mediators and military leaders at State House, his presidential headquarters. On Friday, it even allowed him to supervise a university graduation ceremony.

Nov. 16: A screengrab from Zimbabwe Broadcasting Corporation shows Mr. Mugabe, second from right, with General Constantino Chiwenga, right, and South African envoys in Harare.

ZBC/AFP/GETTY IMAGES

This strategy might avoid bloodshed and pave the way for a peaceful transition to a new government – but it does nothing to restore democracy in a country where autocrats have long ruled.

"A family had captured the state, and now a junta is capturing the state," Mr. Gwede said. "It doesn't change the fundamentals. We're still under a militarized and undemocratic system that doesn't respect human rights. We're seeing how the military has become such a powerful force in our politics. It's hard to see who can run the country in the future without the army, and that's not what we want as human rights defenders and democrats."

He wonders if the military will allow any criticism of the next president – whether it is Mr. Mnangagwa or someone else. "It's as if the military are the commissars of the ruling party. They're not acting as a national army – they are acting as a partisan party. And that's dangerous."

AFP/GETTY IMAGES

Geoffrey York is The Globe and Mail's Africa correspondent.

MORE FROM THE GLOBE AND MAIL